In an era where data is increasingly viewed as a cornerstone of national power, Canadian AI Minister Evan Solomon has unveiled a groundbreaking proposal for a sovereign cloud, aiming to shield the nation’s information from foreign control and bolster autonomy in the AI-driven economy. This initiative arrives amid escalating concerns over data security, particularly with laws like the U.S. CLOUD Act enabling American authorities to access data stored on U.S.-owned servers, regardless of location. Solomon’s plan promises to redefine how Canada manages its digital assets, positioning the country as a potential leader in balancing security with innovation. Yet, as expert Don Lenihan, a specialist in digital transformation, suggests, this vision carries both significant potential and notable risks. Delving into the nuances of this tripartite data security model reveals a complex interplay of strategic intent and practical challenges that could shape Canada’s technological future.

Breaking Down the Proposed Framework

A Tiered Approach to Data Security

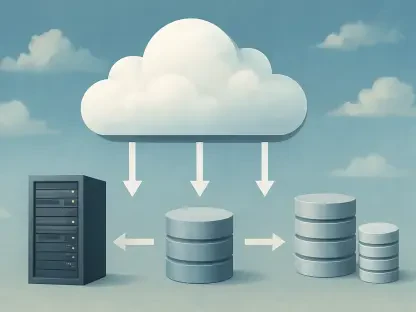

Solomon’s strategy hinges on a three-tiered system designed to address varying levels of data sensitivity, from critical national security information to everyday public datasets. The fully sovereign cloud, the first tier, targets highly sensitive data, ensuring it remains on Canadian soil under strict domestic control. The hybrid model, the second tier, focuses on economically vital information, allowing collaboration with foreign tech firms under Canadian oversight. Lastly, the public cloud manages non-sensitive data with minimal restrictions. This structure reflects a thoughtful attempt to safeguard national interests while engaging with global technological advancements. However, Lenihan points out that while the framework appears robust on paper, certain elements, particularly the hybrid tier, may inadvertently undermine the very sovereignty it seeks to protect by fostering dependency on external players.

Assessing Strategic Intent and Feasibility

The overarching goal of Solomon’s proposal is to position Canada as a self-reliant player in the global AI landscape, treating data as a national asset akin to historical resources like timber or oil. This vision aligns with the urgent need to transition from a digital era of mere storage to an AI-driven economy where data fuels innovation in sectors such as healthcare and sustainability. The tripartite model aims to balance protection with practicality, acknowledging that complete isolation from global tech infrastructure is neither feasible nor desirable. Yet, Lenihan’s critique highlights a critical concern: the risk of entrenching reliance on American tech giants, whose dominance in cloud services could fragment Canadian data into silos. This tension between security and access to cutting-edge tools underscores the complexity of achieving true autonomy in a highly interconnected world.

Exploring the Three Tiers in Depth

Fully Sovereign Cloud: A Fortress for Critical Data

Solomon’s first tier, the fully sovereign cloud, stands as a bastion for the most sensitive information, including defense, intelligence, and critical infrastructure data. This segment mandates that such data be stored exclusively within Canada, managed by domestic companies, and governed solely by Canadian laws. This approach is seen as a significant strength, offering a robust shield against foreign interference, particularly from risks posed by extraterritorial laws like the U.S. CLOUD Act. Lenihan commends this tier for establishing a clear line of defense, ensuring that the nation’s most vital assets remain beyond the reach of external control. By prioritizing absolute sovereignty in this domain, Solomon’s plan sets a high standard for protecting core national interests, providing a foundation upon which trust in the broader system can be built.

The fully sovereign cloud also serves as a symbol of Canada’s commitment to data autonomy, signaling to both citizens and international partners that the country values its digital independence. This tier avoids the complexities of international collaboration, focusing instead on self-reliance through Canadian infrastructure and expertise. While this approach may limit access to some global technologies due to its stringent requirements, Lenihan notes that such trade-offs are necessary for safeguarding data that underpins national security. The emphasis here is on creating a secure backbone that can support other tiers of the model, ensuring that even as Canada engages with foreign entities elsewhere, its most critical information remains untouchable. This focus on a fortified core is a strategic move in an era where data breaches can have catastrophic consequences.

Hybrid Model: A Double-Edged Sword

The hybrid model, the second tier of Solomon’s framework, targets economically significant data across sectors like health, finance, energy, and research, allowing American tech firms such as Google and Microsoft to manage it under Canadian legal oversight and encryption safeguards. This tier aims to mitigate risks from foreign laws by imposing strict controls, ensuring that while international expertise is leveraged, Canadian jurisdiction remains paramount. However, Lenihan warns that this model could deepen dependency on these tech giants, whose proprietary systems often lock institutions into long-term reliance. Canadian entities like hospitals and banks, already using platforms like Microsoft Azure or Google Cloud, face challenges in switching providers or integrating data across sectors, stifling the collaborative innovation needed for large-scale advancements.

Further scrutiny reveals that the hybrid model’s reliance on foreign infrastructure risks creating a digital equivalent of the historical branch-plant economy, where Canada hosts the facilities but cedes strategic control to external entities. Lenihan argues that this setup fragments valuable datasets into vendor-specific silos, hindering the cross-domain integration essential for breakthroughs in areas like smart cities or personalized medicine. While Solomon’s intent to balance security with access to advanced AI tools is pragmatic, the long-term cost could be a diminished capacity to shape national outcomes using domestic data. This critique suggests that without mechanisms to prioritize Canadian firms or foster interoperability, the hybrid tier may undermine the broader goal of sovereignty by embedding foreign influence at the heart of the nation’s economic data landscape.

Public Cloud: A Low-Stakes Solution

The third tier, the public cloud, manages non-sensitive data such as weather reports and street maps, operating with fewer restrictions and allowing broader access to global services. This segment is largely uncontroversial, as it poses minimal risk to national security or sovereignty, focusing instead on practicality and efficiency. Lenihan notes that by allocating non-critical information to this tier, Solomon’s model sensibly conserves resources, avoiding overregulation where it’s unnecessary. This approach ensures that everyday data remains accessible to the public and businesses alike, facilitating routine operations without the burden of stringent controls applied to more sensitive categories.

Moreover, the public cloud reflects a realistic acknowledgment of the interconnected nature of modern technology, where complete isolation is neither possible nor beneficial for less critical datasets. This tier allows Canada to tap into the vast capabilities of global platforms without compromising core national interests, striking a balance that supports both user convenience and system efficiency. Lenihan highlights that while this tier lacks the strategic weight of the others, its inclusion in the framework demonstrates a nuanced understanding of data’s diverse roles. By delineating clear boundaries for what requires protection versus what can be openly shared, Solomon’s plan ensures that the focus remains on safeguarding what truly matters while maintaining flexibility in less consequential areas.

Broader Implications for Canada’s AI Future

Innovation Versus Dependency: A Defining Challenge

A central tension in Solomon’s proposal lies in the clash between fostering innovation and avoiding dependency on foreign technology providers, particularly within the hybrid model where most economically vital data resides. Lenihan emphasizes that while the framework addresses immediate security concerns through legal and encryption measures, it falls short in building Canadian capacity to rival global AI leaders. Without a deliberate push to nurture domestic firms or create spaces for them within the hybrid tier, Canada risks remaining a secondary player, reliant on American giants whose business models prioritize siloed control over shared progress. This dynamic could limit the nation’s ability to leverage data as a public resource, stunting transformative advancements in key sectors like healthcare and sustainability.

Addressing this challenge requires more than just protective measures; it demands a proactive strategy to enhance Canada’s technological self-reliance over the coming years. Lenihan’s critique suggests that treating data as a collective asset, akin to public infrastructure, could pave the way for policies that incentivize local innovation while still engaging with global tools. The absence of such a focus in Solomon’s current plan highlights a missed opportunity to align security with long-term economic goals. As Canada navigates its role in the AI economy, finding ways to break free from vendor lock-in and promote cross-sector data integration will be crucial. This balance is not easily achieved, but it remains a defining issue that Solomon’s vision must tackle to ensure true sovereignty.

Building a Path Forward: Strategic Next Steps

Looking ahead, the critique of Solomon’s sovereign cloud model points to the need for actionable strategies that go beyond the current framework’s focus on security. One potential direction is the establishment of dedicated initiatives to support Canadian AI startups and tech firms, ensuring they have the resources and market access to compete within the hybrid space. Lenihan’s analysis implies that government investment in domestic infrastructure and interoperability standards could counteract the fragmenting effects of foreign silos, enabling data to flow more freely across sectors for national benefit. Such steps would require significant policy coordination and funding, but they are essential for transforming data sovereignty from a defensive concept into a driver of innovation.

Additionally, fostering public-private partnerships could help bridge the gap between immediate needs and long-term autonomy, allowing Canadian entities to collaborate with global firms while gradually building local expertise. This approach would mitigate the risks of dependency by setting clear timelines and benchmarks for transitioning key services to domestic providers. Solomon’s plan, while a strong starting point, must evolve to incorporate these forward-thinking measures, ensuring that Canada not only protects its data but also harnesses it to shape a future defined by self-reliance and global competitiveness. As discussions around this vision continue, the focus should remain on crafting solutions that empower the nation to lead rather than follow in the AI era.