U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement is quietly moving to integrate the powerful data-gathering tools of the commercial advertising industry into its surveillance operations, signaling a significant escalation in the use of consumer-level data by federal law enforcement. A recent Request for Information (RFI) published by the agency explicitly solicits “commercial Big Data and Ad Tech” products, a move that formally seeks to repurpose technologies designed for marketing into instruments of state investigation. This development raises profound questions about the erosion of privacy, the exploitation of legal gray areas, and the future of civil liberties in a world where personal data has become a readily available commodity for government agencies. The agency’s initiative represents a deliberate effort to harness the vast, unregulated ecosystem of consumer data to enhance its enforcement capabilities far beyond traditional investigative methods.

A Strategic Shift Toward Commercial Surveillance

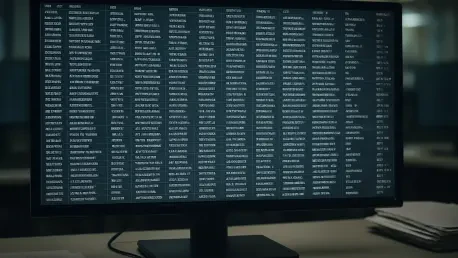

The explicit inclusion of the term “ad tech” in an official federal procurement document marks a watershed moment for ICE and a clear indication of a strategic pivot in its surveillance methodology. This is not merely an incremental upgrade but a foundational shift, demonstrating that the agency views the sophisticated tracking and profiling capabilities developed for digital advertising as directly applicable and essential to its law enforcement and immigration missions. The RFI’s stated objective is to acquire tools that can “directly support investigations activities” by helping the agency manage, analyze, and derive insights from the immense volumes of data it collects from a multitude of internal and external sources. This formal request to the market indicates that what was once a covert or opportunistic practice is now being pursued as a core, institutionalized strategy for expanding the agency’s investigative reach through commercial technology.

This development formalizes the convergence of commercial surveillance and government law enforcement, a scenario long warned of by privacy advocates. Tools originally engineered to monitor online habits, track physical movements, and profile consumer behavior for targeted marketing are now being openly sought for state surveillance, often without the constitutional safeguards that have traditionally governed police investigations. The RFI underscores the agency’s intent to exploit a well-known legal loophole: while a warrant is typically required to obtain a person’s location data directly from a telecommunications carrier, purchasing the same, or even more detailed, information from a commercial data broker has long existed in a legally ambiguous space. ICE’s solicitation suggests a desire to not only continue but also to systematize and expand its use of this loophole, effectively bypassing established legal processes by treating constitutionally protected information as a simple commercial transaction.

The Existing Architecture of a Digital Dragnet

This new request for information does not exist in a vacuum; it is intended to build upon an already robust and deeply integrated surveillance infrastructure that is heavily reliant on commercial data and powerful technology partnerships. A cornerstone of this system is the agency’s longstanding contract with the data analytics firm Palantir for its Gotham platform. This software has been customized into an “Investigative Case Management” (ICM) system that acts as the central nervous system for ICE’s data operations. Within this expansive ecosystem, a tool known as FALCON allows agents to store, search, and visualize immense quantities of disparate investigative information, from government records to commercially sourced data, creating a comprehensive digital picture of its targets. This existing framework demonstrates that ICE is not just beginning to explore big data but is seeking to supercharge a mature and powerful surveillance machine with even more intrusive data streams from the ad tech world.

Beyond its sophisticated data management platforms, ICE has been an active and aggressive procurer of raw location data from the commercial market, directly linking its operations to the ad tech ecosystem. The agency previously purchased access to Webloc, a product from Penlink that enables dragnet-style surveillance by collecting and mapping mobile phone location data within specific geographic areas and timeframes. Significantly, Webloc allows users to filter this vast trove of data by its source—such as GPS, WiFi, or IP address—and even by specific Apple and Android advertising identifiers, which are unique codes assigned to individual devices for tracking purposes. Furthermore, ICE has been a client of Venntel, a data broker owned by Gravy Analytics, which specializes in aggregating and selling consumer location data that has been quietly harvested from thousands of ordinary mobile applications, turning everyday smartphone use into a potential source of intelligence for federal agents.

Navigating a Shifting and Tense Environment

ICE’s push to expand its technological arsenal is occurring within a complex and increasingly volatile regulatory environment, where the practices of data brokers are facing unprecedented scrutiny. The case of Venntel serves as a prime example of the legal and ethical challenges involved in this domain. In 2024, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) took decisive enforcement action against Venntel’s parent company, Gravy Analytics, alleging that it sold highly sensitive consumer location data for both commercial and government use without obtaining proper and informed consent from individuals. While the company did not admit to the allegations, the FTC’s subsequent order barred it from selling sensitive location data, except under specific circumstances related to national security or law enforcement. This regulatory action, however, appears to have done little to deter ICE. Instead, the agency’s new RFI suggests it is now surveying the market for alternative vendors or more expansive capabilities that may be considered compliant, effectively seeking to navigate around these new regulatory hurdles.

The timing of ICE’s filing is particularly striking, as it was published just before a fatal incident in Minneapolis where a Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officer, working on a joint operation with ICE, shot and killed a 37-year-old man. This event has intensified public scrutiny of immigration enforcement tactics and put additional pressure on federal agencies to justify their methods and demonstrate accountability. By quietly seeking to expand its technological capabilities at a time when its physical enforcement actions are under intense public and political fire, ICE appears to be deepening its reliance on less visible but highly invasive forms of digital surveillance. This parallel escalation suggests a strategic decision to augment its on-the-ground operations with a powerful and less transparent digital dragnet, further insulating its investigative methods from public view while simultaneously expanding their scope and power.

The Institutionalization of a Surveillance Playbook

The evidence made it clear that ICE had systematically and openly moved to incorporate the tools of the commercial ad tech industry into its core investigative framework. The agency’s Request for Information was not merely an inquiry but a definitive signal that the trend of law enforcement bypassing warrant requirements by purchasing commercially available data was accelerating and becoming institutionalized. This development created a direct conflict between the rapid, unregulated evolution of surveillance technology and the much slower, more deliberate pace of privacy law and constitutional protections. The future of digital privacy and civil liberties in the United States ultimately depended on whether legislative bodies would intervene to close the commercial data loophole before it became the standard, accepted playbook for federal law enforcement investigations nationwide.